EU and UK climate disclosure programmes: an overview

Published • Last updated

Governments are asking companies harder questions about climate action, with Europe leading the way. While the EU and UK already require large companies to report some energy and emissions data, these programmes are expanding in what they ask and whom they ask it from.

Many companies find it difficult to track all the new acronyms and understand exactly what’s required of them. But if you operate in the EU or UK and have 250+ employees or significant revenue and balance sheet, you likely need to start reporting advanced disclosures by 2023—including precise emissions across your full supply chain and detailed plans of how you’re going to reduce them this decade.

This guide—which we’ll keep updated as rules evolve—breaks down the main programmes: what they require, when they require it, and how they’re expected to change.

Watershed helps companies build high-impact, compliance-ready climate programmes. If we can help with anything from measurement to reductions to reporting, please get in touch.

Terminology 101

A few key terms you’ll find throughout this post:

- TCFD is a set of 11 questions that’s fast cementing itself as the global baseline for climate disclosures. While many programmes now require more than just TCFD answers, these answers are a reporting backbone that can be reused in multiple places.

- Green taxonomies are the new regional rulebooks that determine which business inputs can be counted as officially green—from energy sources to office fittings. Investors will soon be asking portfolio companies how green they are by these rules.

- Scopes 1-3 are how the GHG Protocol (the gold standard for climate accounting) categorises greenhouse gas emissions. Scope 1 emissions come directly from fleets and factories you operate, Scope 2 represents electricity/heating/cooling you purchase, and Scope 3 covers everything emitted by suppliers and customers across your value chain. Most new disclosure programmes ask companies to include Scope 3 emissions.

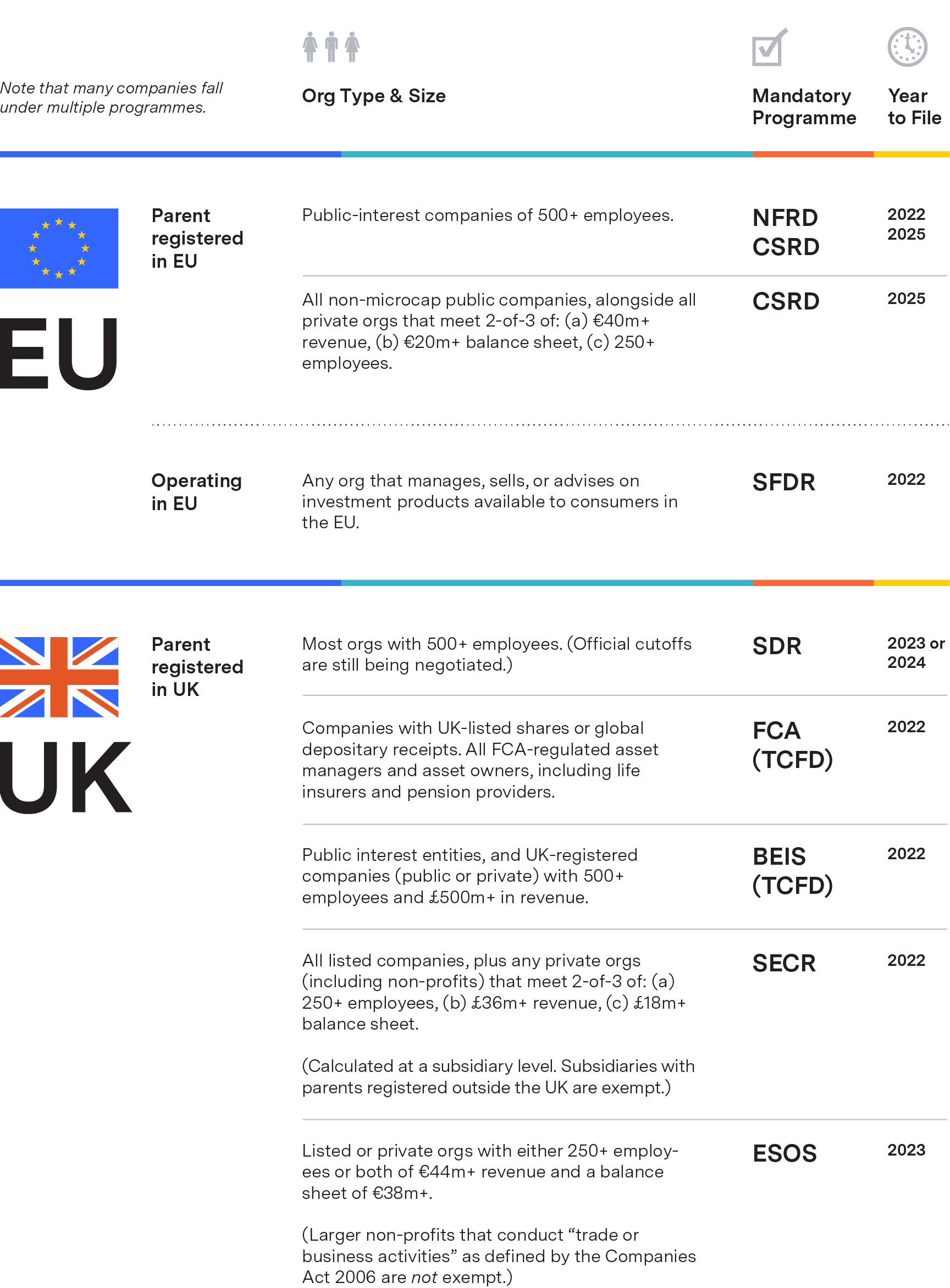

Disclosure programme summary

The European Union

The EU has adopted an ambitious “net zero by 2050” master policy plan, and is currently replacing their old climate disclosure regime (NFRD) with a new suite of programmes that will require all but the smallest companies to report on—and aggressively reduce—their emissions.

NFRD - Non-Financial Reporting Directive

The EU’s primary—but aged—ESG disclosures programme. While revised in 2019 to include TCFD questions, the update was optional for filers, and further adjustments have been shelved in lieu of a replacement programme (CSRD) set to be finalised in late 2022 or early 2023.

What it requires

Filers must provide “information” (imprecisely defined) on process and outcomes related to the environment, human rights, employee treatment, anti-corruption efforts, and board diversity.

How it’s submitted

Organisations are free to report the required information in line with a number of popular interpretations / approaches (e.g., GRI, OECD, ILO, or ISO 2600).

Where it’s going

NFRD will soon be replaced by a more defined and more demanding successor programme, CSRD (see next section). While the first reporting year for CSRD likely won’t be until 2024, Watershed strongly advises advance preparation—particularly measuring supply chain emissions and having a concrete plan to reduce them.

CSRD - Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive

The EU’s new master ESG disclosures programme, designed around their vision for an era of robust social action, particularly around climate. CSRD will replace NFRD (see prior section) in 2023, and is expected to roughly quadruple the number of covered organisations—many of which will be reporting in depth on their carbon emissions for the first time.

What it’s going to require

While a working group is currently finalising the rulebook, it’s expected to add the following climate-centric disclosures to NFRD’s baseline:

- Answers to the 11 core TCFD questions

- Detailed energy consumption data

- Scope 1-3 greenhouse gas emissions (actuals and forecasts)

- Intensity ratios (i.e., measuring absolute emission and consumption quantities against fixed metrics like revenue)

Organisations already reporting under NFRD will need to submit their first CSRD filing in 2025 (covering 2024 data). Newly eligible companies that never met the NFRD criteria can file a year later, or two years later if they're a publicly-listed SME. Though investors and other stakeholders are likely to ask for many of these inputs far in advance of those dates.

How it’s going to be submitted

CSRD disclosures will require auditing, and for the formatting to be machine-readable so that submissions can be aggregated into a single EU-wide database. While exact rules are forthcoming, it will be a single document that combines financial and non-financial information.

Where it’s going

A first draft of the rules was targeted for late 2022, but may be delayed into 2023 as the EU seeks to harmonise their efforts with the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), who are working in parallel to create a global framework that mixes TCFD questions with non-climate ESG disclosures.

SFDR - Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation

The EU’s programme for creating ESG “nutritional labels” for financial products and the firms that market them—giving buyers and investors context on climate impact and any associated risks. SFDR will pair closely with the EU’s Green Taxonomy (see next section), the new rulebook on what counts as officially green.

What it requires

The programme has two “levels” of rules. The first came into effect on 21 March, 2021, and the second is expected to be put into force in 2023.

(What follows is a simplified summary of a highly nuanced ruleset. For precise details, please see the official rulebook, or get in touch with one of our programme specialists.)

-

Level 1 disclosures = “your product’s disclosure docs must cover a defined list of sustainability / ESG risks” plus “your firm must have similar disclosure docs so that potential clients can evaluate you as a counterparty”

-

Level 2 = “you have to be explicit about the degree to which each individual product is compliant with Articles 6, 8-9”

-

Article 6 (“amber”) products factor ESG in some way, but don’t pass the EU’s Green Taxonomy and related tests as green enough

-

Article 8 (“light green”) products pass the tests, but don’t have ESG as a core objective

-

Article 9 (“dark green”) products pass the tests and do have ESG as a core objective

-

How it’s submitted

Depending on the firm and product, SFDR disclosures can fall into three reporting categories:

- Public (i.e., mandatory online disclosures)

- Pre-contractual (i.e., a brief provided to prospective customers)

- Periodic Reports (largely annual)

For firms that weren’t in the first wave, the programme’s first major filing date is 30 June, 2022. First-time filers only need to submit the qualitative portions as outlined here—which must specify which quantitative measures will be tracked and disclosed starting in 2023.

Where it’s going

While SFRD is officially an EU-wide programme, some further country-level customisation is still expected. Discussions are also still ongoing around Level 2 specifics and how to harmonise the timelines with CSRD (as investors are being required to ask their portfolio companies for information that those companies haven’t yet had any regulatory reason to collect).

United Kingdom

The UK is positioning itself as a leader on ESG and climate reporting, and is replacing their pre-Brexit rules with far more comprehensive requirements—covering Scope 3 emissions and the specifics of how you’re going to reduce them.

SDR - Sustainable Disclosure Requirement

SDR was designed to centralise the UK’s new enhanced climate and ESG reporting regimes. The other programmes covered in this guide (all but ESOS) are expected to collapse into SDR once its rules are finalised. Though this isn’t expected until 2023, SDR will ask companies for far more detailed data and plans, and Watershed recommends starting on compliance early.

What it’s going to require

- Answers to the 11 core TCFD questions. (While TCFD currently allows companies to choose whether they’ll cover Scope 3 supplier emissions, SDR is expected to require it.)

- Answers to other non-climate ESG questions (including impact on nature more broadly).

- A detailed transition plan outlining the submitter’s path to net zero emissions.

For items 1 and 2, it’s likely that SDR will mandate “double materiality” (i.e., not just how climate change may affect a business, but how that business’ operations are likely to affect the climate).

How it’s going to be submitted

While the formatting requirements and supporting guidance for these disclosures have yet to be finalised:

-

Companies required to produce a “non-financial and sustainability information” (NFSI; formerly NFI) statement will be asked to add their SDR disclosures there.

-

Companies with no NFSI requirement can insert their disclosures in either their SECR report (see next section) or their annual strategic report, as suits their situation.

Where it’s going

While SDR is moving forward with initial rulemaking and will emerge as the definitive UK standard, they’re also working to stay aligned with two parallel efforts:

- The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), which was created by the UN to create a global framework that mixes TCFD with non-climate ESG disclosures.

- The UK’s Green Taxonomy (see final section), which is still being written.

In the interim, large UK businesses will mostly be asked to report on climate via a mix of ESOS, SECR, and the existing TCFD-based programmes covered in the next section.

The TCFD Roadmap

While SDR rules are being finalised, many institutions are still required to submit TCFD answers under a patchwork of prior directives from the FCA and other executive bodies.

1. FCA - Financial Conduct Authority

Companies that issue UK-listed shares or global depositary receipts must either answer TCFD’s core questions in their annual financial reports or include a statement as to why they haven’t. Applicable to accounting periods starting on or after 1 January, 2022.

FCA-regulated asset managers and owners have to publish a pair of annual TCFD reports in a prominent place on their websites: one entity-level report covering the firm’s operations, and one covering their products and portfolios. Phase 1 applied starting 1 January, 2022. (More details on phasing in Appendix 1 here.)

2. BEIS - Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

Covered organisations have to disclose answers to eight TCFD-esque questions via the non-financial and sustainability (NFIS) statement within their Strategic Report, else via the Energy and Carbon Report section of their standard Annual Report. Applicable to accounting periods starting on or after 6 April, 2022.

SECR - Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting

Formerly known as the Energy Efficiency Scheme or Carbon Reduction Commitment, SECR is the main programme by which UK companies have reported their emissions to date. It’s expected to fold into the Sustainable Disclosure Requirement regime in 2023–2024.

What it requires

- Total energy consumption and all Scope 1+2 greenhouse gas emissions

- One intensity ratio (e.g., emissions relative to a fixed business measure like revenue)

- Brief commentary about anything done recently to increase energy efficiency

For publicly-listed companies, this extends to their global footprint, while private organisations need only report on UK operations. Though private companies/LLPs also need to disclose fuel consumed for most ground-based business travel.

How it’s submitted

As a templated subsection in annual reports to Companies House.

Where it’s headed

There are planned 2022 consultations about collapsing SECR into SDR (see above).

ESOS - Energy Savings Opportunity Scheme

A legacy programme inherited from the EU that requires an energy audit every four years (next in 2023). While ESOS is still being rewritten post-Brexit, it’s expected to require additional disclosures (including emissions), and to apply to an even broader swathe of companies.

What it originally required

Covered organisations were asked to measure and document their total energy consumption across their buildings, industrial processes, and transportation use—along with commentary on:

- Which business areas consumed the most energy

- How they plan to reduce consumption in those areas

- What other reductions they’ve considered

- Who the lead assessor (auditor) and board-level reviewer were

How it was submitted

For past four-year cycles, there was no set audit format and no submission requirement for any findings. Companies were merely asked to send notice that an audit had been completed, and to keep whatever records they had for potential inspection.

These rules are being revisited ahead of the relevant upcoming dates for the upcoming cycle:

- An organisation’s eligibility will be determined by their size on 31 Dec, 2022

- Covered organisations will have to file their submissions by 5 Dec, 2023

- Submissions must cover 12 consecutive months that include the eligibility date

Where it’s going

ESOS’s post-Brexit revamp is expected to be completed by late 2022. The government is hoping to address a few things at once—which will be applicable to all 2023 filers:

-

A shift from driving energy efficiency to also driving decarbonisation (which means measuring carbon emissions alongside energy use)

-

An expansion to cover some 30,000 additional medium-size businesses

-

Stronger requirements around actually implementing the recommendations surfaced by the audits (which to date have been largely voluntary)

A note on taxonomies

A green taxonomy is a definitive scoring system that assigns a pass/fail green value to various business inputs—like energy sources and building efficiency ratings. It allows for a fixed legal answer to the question “can I claim to customers or investors that this thing is actually green”.

EU Green Taxonomy

All EU financiers will soon be looking at their portfolios through the lens of this new taxonomy to determine what’s green enough to meet various regulations and climate goals. And as regulators want to get tougher on emissions, they’re likely to adjust what qualifies as green and/or demand that funds have a higher concentration of green assets.

The system starts with six environmental objectives that truly green activities should support:

- climate change mitigation

- climate change adaptation

- sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources

- transition to a circular economy

- pollution prevention and control

- protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems

Alongside three mandatory conditions:

- makes a substantial contribution to at least one objective

- does no significant harm to any objective

- complies with minimum social safeguards

If an activity passes all three conditions, it’s EU green, or “taxonomy-aligned”. Though if it fails, it may still qualify as a transitional or transition-enabling activity, which would secure it a three-year temporary green rating (e.g., a wind turbine manufacturer that’s reliant on dirty power would have that grace period to green their operations).

Some practical notes:

- Each activity will be green/not green based on an assigned threshold (e.g., solar panels must emit less than 100g/kWh).

- There’s currently no formal distinction between things that fail the taxonomy and those outside its scope, resulting in an unintentional penalty for companies that perform activities not yet covered. Some have proposed formalising a “brown taxonomy” to cover the former, where regulations can then say “you need x% green and no more than y% brown” and activities not covered can be effectively neutral. This is still being evaluated.

- While the first draft of the EU’s taxonomy (which only fleshed out the first two objectives) has been in force since 1 Jan, 2022, there are still large questions being hotly contested (eg., nuclear power and natural gas usage), and the other sections are still forthcoming.

- There’s also a parallel social taxonomy being negotiated that would apply similar principles to objectives like promoting employee health, jobs, and human rights. The desired end state is that every EU product and service will come with a broad ESG nutritional label with mandated minimums/maximums of various “ingredients”.

Though companies largely aren’t required to respond to the Green Taxonomy directly, an increasing number—whether directly or through an investor—will be subject to ESG programmes that mandate disclosure of how taxonomy-aligned various business inputs are.

UK Green Taxonomy

The UK is currently working on their own taxonomy (target late 2022), which will take the EU’s structure and apply its own scoring thresholds based on the UK’s priorities and political context (i.e., where it will be easier or harder for locally controversial activities to get a green rating).